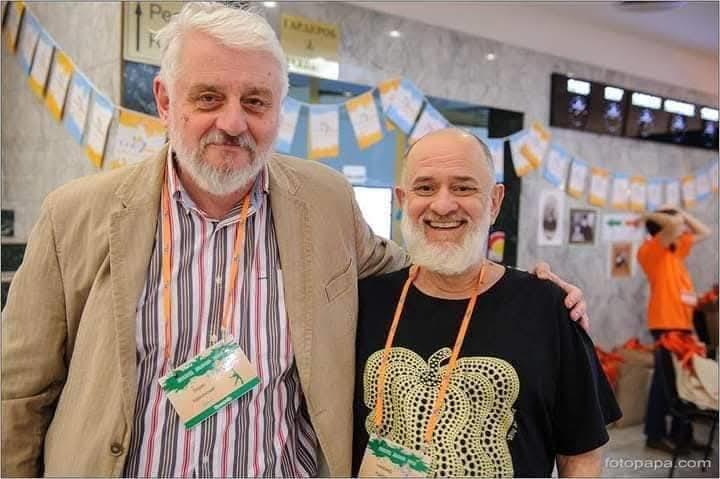

Main image: Boris Khersonsky

Seventh interview through poetry by Andriy Sheptunov

His name has long become synonymous with the intellectual spirit of Odessa — that very blend where irony lives side by side with tragedy, and philosophy never detaches itself from the pulse of human experience. Born in 1950 in Chernivtsi, Boris Khersonsky grew up in Odessa — a city that became part of his inner landscape and poetic voice forever.

Khersonsky is a rare fusion: M.D., Ph.D., Rector of the Kyiv Institute of Modern Psychology and Psychotherapy (since 2017). He established the Department of Clinical Psychology in Odessa and headed it until he moved to Kyiv. He is an Honorary Academician (CA, Belgium), and at the same time one of the most recognized Ukrainian poets of our time.

His poetry reads like a diary of the soul, where the personal merges with the historical, and a family’s fate turns into a metaphor for the fate of a nation. His lines breathe with biblical echoes, Odessa’s streets, Jewish memory, and post-Soviet irony.

He writes as if speaking — calmly, reservedly, but each word carries the weight of lived experience. His works have been translated into many languages and received numerous literary awards. Khersonsky has represented Ukraine at international festivals more than once.

Today, Boris Khersonsky remains one of those rare authors who can speak about pain — without pathos, about faith — without preaching, and about time — without a calendar. His poetry is a way of remembering who we are when everything around us is changing.

In his verses, one can always feel the breath of time — sometimes anxious, sometimes piercingly quiet. His poetry looks directly into the essence of things, unafraid of contradictions, preserving humanity where it so often seems lost.

Our conversation with Boris Khersonsky is a special one. The poet answers questions not only with words, but also with poems. His responses are not rational explanations, but poetic reactions — as if every answer passes through the filters of rhythm, memory, and feeling. It is not a dialogue “by points,” but a conversation between the soul and time.

Interview

1. How do you perceive the war in Ukraine — as a citizen, as a poet, and as a person for whom the word has always had healing power?

I see war, first of all, as a tragedy. As a guarantee of crimes. As a release of aggression accumulated for decades. And, sadly, as an inevitability. I used to joke grimly: my grandfather survived three wars, my father — one. Why should there be none in my long lifetime? I had a premonition of war even before 2014.

It was reflected in my poems of that period. The source of danger was also clear — russia. The attack on Georgia in 2008 drew a line under my views of the post-Soviet “drunken Rus.”

Could a more reasonable policy by our government have prevented the war? It could have postponed it. But not prevented it. Ukraine’s independence was unbearable for traditional Russian ideology — the “Third Rome” theory. It was an amputation of roots, five centuries of history that Moscow had appropriated — and now the stolen is being reclaimed.

Last night there were explosions, fires and light glares.

Antiquity was targeted by Century Twenty-One.

Daily worries are no sweeter than nightmares.

Every terrible tragedy is followed by comedy fun.

(Tristia 265)

2. What is happening to modern reality — does it destroy poetry or make it more necessary?

Interest in poetry declined long before the war — just as interest in classical music and old painting did. As my musicologist friend once said, “All that has ceased to be a fact of public consciousness.” It sounds pompous, but it’s true.

It’s a rather peaceful divorce — mutual — between poet and reader. The destruction of traditional poetic forms, without which modern poetry cannot exist, shocked the audience. This applies to contemporary art as a whole. Sometimes I feel that poetry has died, and we are merely dealing with the products of its decay.

There’s an ongoing discussion about the “death of the author,” which has deepened with the rise of AI. But I remember the metaphor of Jesus: if a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it bears much fruit. I’m sure poetry will be renewed through its current crisis.

I only fear that two types will remain: functional and elitist. “Poetic advertising,” song lyrics, verses for anniversaries, deaths, and victories — all that will exist not for the reader, but for the listener.

The world makes no sense, to absurdity it evolves.

Descending into Hell’s no worse than ascending Parnassus,

where myriads of poets howl like a pack of wolves.

(Tristia 571)

3. What does it mean to be an Odessa poet today, when both the city and its spirit are changing so rapidly?

Now I’ll say something I probably shouldn’t. I lived in Odesa almost all my life and wrote a lot about it. But something went wrong. My relationship with the city’s cultural elite never worked out.

As my friend once said, “In Odessa, Khersonsky and his poetry are not loved.” In twenty-five years, not a single one of my books was published in the city, while over thirty were published elsewhere in Ukraine and abroad.

Only my friend Oleksandr Roytburd could “compete” with me in being equally unwelcome in Odessa. And though much has changed, this silent resistance remains. The city can easily do without me — but I cannot do without the city. Love is not always mutual, is it?

Constanza does not exist. And there isn't an airport.

Only Rome exists. And Rome is extremely ancient.

It's strange to have city government in such minor locations!

There should be a village council. And hordes of Sarmatians.

(Tristia 265)

4. Your poetry often turns to God. Is it an inner dialogue, an attempt to understand, or a form of resistance to absurdity?

Both more complicated and simpler. I’m a believer. God’s presence in the world echoes His presence in my soul. In youth, everything was clearer; in recent years, things have become more complex, not without crises. Religion is increasingly turning into a political tool — in russia, it’s obvious; but in Ukraine too, the church is deeply involved in politics.

Still, faith and religious culture remain vital to me. I would say that theology and prayer are elements of my poetry. The closer a poem is to prayer, the better it is.

What have you achieved by bowing before the crucified Jew?

Is your pontiff a priest or a warrior? What’s in it for you?

(Tristia 571)

5. How has your perception of time changed — before and after the war?

Time is one of the main heroes of my poetry — the river of time, History, Clio… The central project of my life is a journey of a person through time, wandering across centuries, moving from one civilization to another, a surreal intertwining of eras. This became “Tristia” — five books of elegies, each with one hundred poems. Every elegy consists of five ten-line stanzas — 25,000 lines in total.

- Out of Time

- Time Machine

- Labors and Days

- Meridians and Parallels

- Stumbling Stones

The first three have been published (two sold out, one last copy remaining). The final two await editing and publication — hopefully by the end of this year.

My years join the waters of the Pontus Euxinus.

I often watch the sunrise to reinforce.

What’s beyond the horizon line? Is it true that the rest is silence?

The rotation of time presses with its centrifugal force.

Tristia 265)

6. What matters more to you: memory or oblivion?

A simple question. Memory, of course. Especially the long-term kind.

We are dissolved in the ruins. They are dissolved in us.

(Tristia 571)

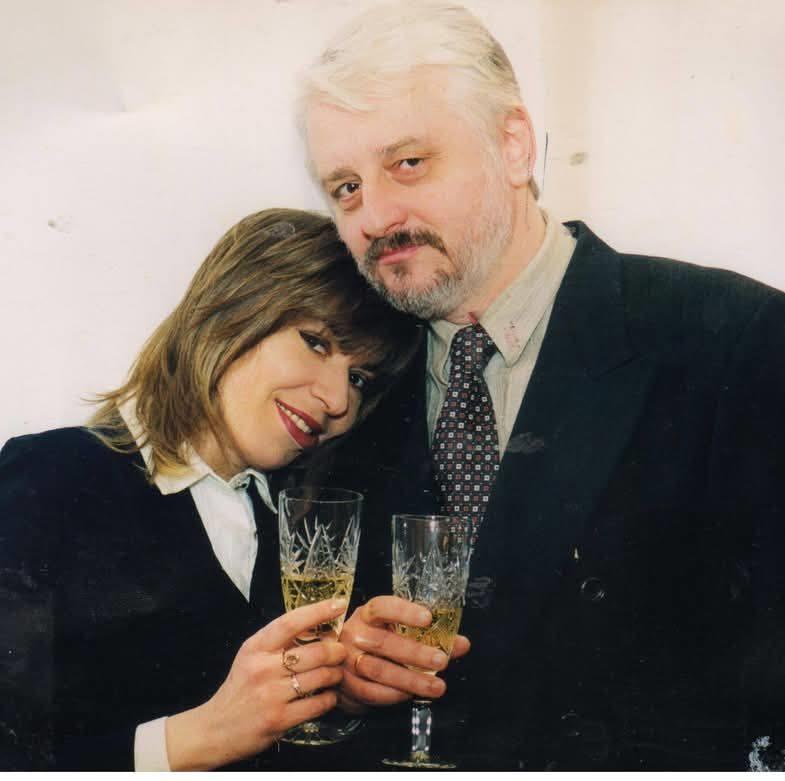

7. What role do women play in your poetic world — muse, mirror, equal companion, or image of loss?

Although philosophical and reflective lyrics dominate my work, love poetry is one of my most important themes. I’ve been lucky: my muse is my life partner — my

mirror, my equal interlocutor. It can all be called love, simply put. As for loss — yes, the death of my mother remains an unhealed wound.

My obstinate temper separated me from my first wife.

The furious temper of the second one avenged me in full.

The third one made me happy, like none of the erstwhile…

(Tristia 1)

8. Do you ever get tired of words?

Not yet. That moment still lies ahead.

I’m not straightforward. I never was. Will I be absolved?

The straight line makes me move in a crooked way.

Truth cannot be found among moral decay.

(Tristia 265)

9. Do you feel more Ukrainian, Jewish, or simply human?

Not simply. My identity is mosaic — a tension between its elements gives me inner energy. Someday it may reach harmony, and then I’ll say to myself: stop. You’ve said everything you wanted to say.

A person is human among people. Among cattle he’s cattle,

A snake in the serpentry, in a pack to a wolf he degrades.

Tristia 1)

10. Are there poems you would rewrite now, because the world has changed?

Mostly those about war. The nature of war has shifted. Some early poems have lost relevance — but one should never write for the sake of relevance! Such works are doomed. Don’t rewrite, don’t republish, don’t adapt them — just accept the fact: some poems die before their authors.

Mussolini wanted to revive the Roman Empire, no joke.

He wasn’t a warlord, but an officer digging for roots…

The columns lie side by side – ‘twas a domino effect movement.

(Tristia 571)

11. If you could say one poem to all humanity, what would it be about?

About love and death. “Don’t wear black clothes — adopt a black kitten.” That’s the first line of one of my poems.

Thus, the thunder of cannons drowns the music of the glorious past.

Thus, good understands that evil will always last.

(Tristia 571)

12. Have you ever tried to rhyme the word “coffee”?

Never. Not an easy task. But if I had to:

A horseshoe brings luck — but luck’s not in the shoe.

It lives in the music shared over coffee, by two.

Boris Khersonsky’s poetry is a space where the personal intertwines with history, and irony stands beside prayer. His writing seeks to understand the time we live in — and to preserve humanity within its chaos.

Readers can explore his new poems, essays, and reflections on his social media pages, where he continues to share his thoughts and texts. His voice reminds us that even in the darkest times, poetry remains a way to see the world more clearly.

Boris Khersonsky's Facebook page